SHOOTING DOWN A RUSSIAN STAR

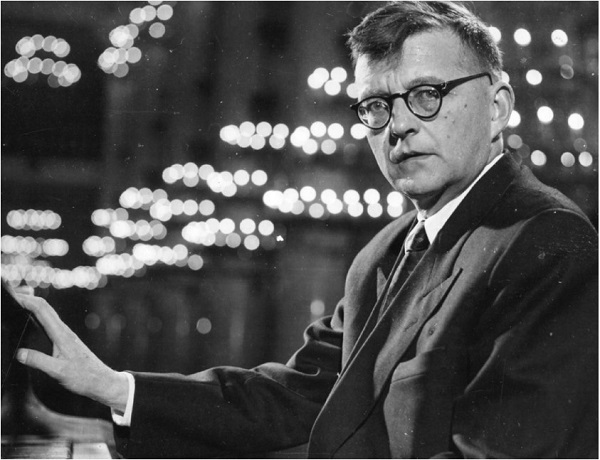

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich, who in his last 22 years was widely recognized as the cream of the crop among the Soviet Union’s composers, arguably turned out most of his significant, insightful music after the 1953 death of his nemesis, dictator Josef Stalin. Stalin had turned music criticism into a personal tool of repression which threatened either gulag confinement or execution to dissidents of any stripe.

Dmitri’s later compositions of greatest note contained his repeated musical signature, D-S-C-H, which indicated via code content which was highly important for him to convey, as his son Maxim later revealed. The D S C H sequence of notes were his shorthand initials in German. He felt that he could never speak his true thoughts about repression of the arts, suppression of music, and the lack of artistic freedom in his land. He had been publicly condemned in the Moscow press for ‘formalism’ and being out of touch with the people’s music in rebukes reputedly written by Stalin himself. Even this D S C H sequence, which we encounter repeatedly in his Symphony No. 10, String Quartet No. 8, and Violin Concerto No. 2, was enough of a giveaway that he never dared premiere these works till after 1953.

A golden opportunity came up in 1966-67 to have the sequestered composer attend a set of concerts of his music in California. The USSR’s elite Borodin String Quartet led by Rostislav Dubinsky, which played on tour at UC Berkeley almost annually, proposed bringing Shostakovich in person with them next time within a festival of his works, featuring him either as a piano performer, lecturer or guest, whatever his health and his overseers back home allowed. This move could have helped cool the seemingly endless Cold War between the two nations. For a sequestered composer rarely allowed trips to the West, it promised a unique event, both politically and musically. The mind boggles considering how such a visit might have led to closer cultural agreements USA-USSR, thereby defusing the danger of a nuclear holocaust through interactive music and musicians.

The bookings at Berkeley were decided by the Committee for Arts and Lectures (CAL). That committee, with its strong representation of the university music faculty, decided astonishingly to decline the stunning offer. As the CAL executive Betty Connors explained it to me, the committee did not feel the music of Shostakovich (1906-1975) to be of high enough quality for such a program. Never mind the political implications, with journalists trooping in from throughout the US to hear and interview this elusive icon from that elusive, tightly controlled Communist nation.

The committee members may well have based their opinions of the earlier works by the composer, doing a period where, to maintain a vestige of freedom, he spent much of his time grinding out film scores for the commissars, and thus avoiding incarceration by the skin of his teeth.

Todayin the West his music is everywhere—from his critique of anti-Semitism called the “Babi Yar” Symphony (No. 13) based on real-life atrocities, to his epic opera staged repeatedly from coast to coast, “Lady Macbeth ofMsensk,” to the output comprising, among others, 15 string quartets and 16 symphonies.

Admittedly, at the time of the offer the introverted 60-year-old composer suffered from both acute nervousness and heart problems. Dubinsky mentioned to me that once in rehearsal of one of the string quartets, contrary to the score they played two notes pizzicato instead of bowed. Shostakovich attending immediately shifted about very uneasily, with his hand going to his mouth. The Borodin players never dared try that again.

But less than two years after the offer, the university did get its stellar (former) Russian composer in the persona of Igor Stravinsky, attending an array of his own works. The rest is (only-in-Berkeley) history.