Old-vs.-New Ballet Crisis Recalled

Carvajal’s Tapping New Social Culture was Anathema

With the 50th Anniversary of the highly innovative and uninhibited “Summer of Love” in San Francisco, we recall the trail-blazing ballet “Genesis ‘70” that resulted not long after. The furor that the here-and-now work produced had been compared to the 1913 Paris premiere of “The Rite of Spring,” which had aroused the biggest riot in ballet history. Recalling the era is the creator of “Genesis ’70,” Carlos Carvajal, a local choreographer still going as strong as ever, this summer serving as co-artistic director of the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival. Here his story, acting as guest columnist.

Upon my recent visits to the museum exhibits of “The Summer of Love” at the De Young and the California Historical Society, I found fine examples of poster art and histories of the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother, Country Joe, and other iconic music groups. Bill Hamm’s light show environment gave a hint as to what his art form was, although it lacked the “in real time” improvisatory component.

I was likewise struck by the paucity of reference to an important element that contributed to the whole tenor of those times— the performing arts of dance and theater. The thriving and varied Bay Area dance community had been intensively experimenting and creating avant-garde theater experiences from the small studio theaters, unusual performance spaces and all the way into the enclaves of the SF opera house.

The Summer of Love’s fiftieth anniversary has been a nostalgic reminder of those wild fashions, colorful posters and musicians of those wonderful times, but there is an important story from those uniquely creative years which has been largely forgotten and untold. What has led up to and followed this celebration of artistic freedom and diversity has given me the desire to enrich the record with my personal experience of these times.

In the fall of 1964 after a ten-year career in Europe, I’d assumed the position of ballet master and associate choreographer for the San Francisco Ballet. I came upon a scene of great innovation and artistic excitement where people, especially the younger generations, were un-self-consciously exploring every art form with great freedom and abandon. They were incorporating light, color, texture, free design, Art Nouveau, popular, classical, new age, electronic and concrete music, dance, and theater into newer, more expressive and dynamic in-real-time multi-sensory public events.

This was the Psychedelic Era, which became publicized around much of the world. It was the age of LSD and other psychotropic substances as well as an ever- growing interest for Eastern wisdom and other systems of knowledge including those of the Native Americans. San Francisco was in the world news as a leader in this new direction. I was motivated, wanting to create a 3D environment of light, sound and texture for my dances that would defy the limits of the proscenium.

The legendary “Light Show” pioneers—Bill Ham, Jerry Abrams, Ray Anderson, Bob Ellison and others—were developing many very primitive but effective real-time techniques using slide and overhead projection equipment as well as 8 and 16 mm movie projectors. The liquid images from overhead projectors [standard public-school equipment at the time] and colored oils were ubiquitous at the rock dances pulsing in time to the music as dancers wildly did absolutely anything they wanted to the songs of the many new rock and roll groups. These artists experimented in many unusual ways to create new visuals including film loops and reflective Mylar. They prepared 35mm slides which were painted and sometimes burnt for effect and projected onto the dance floor and walls of the dance halls, in particular the Fillmore Auditorium at Geary and Fillmore Streets, the Avalon Ballroom at Sutter and Van Ness, and at Winterland, which we frequented on those week-ends after finishing our rehearsals at the ballet.

I was soon able to collaborate with these new media artists in creating several ballets that included their “light show” companies, and I yearned to be among the first to bring such multi-media to the opera house in San Francisco.

There was also the local explosion of new music by Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, John Adams, Warner Jepson, Terry Riley and Phillip Glass which was inspiring new thoughts and images in dance and theater.

For the summer Ballet 66 season, I was inspired to make a dance theater piece relating to the new “Acid Scene” which I called, “Voyage Interdit”, French for “Forbidden Trip”—-the first Rock and Roll ballet. Concrete and electronic music was used as well as stroboscopic lighting effects to enhance the weirdness of the encounters. The dance theater piece was favorably reviewed and brought notice to the public that we at the SF Ballet were responding to the times and producing works relating to the younger generation and its conflict with the “establishment”.

For our 1967 Opera House seasons of the SFB I was able to create world premieres “Kromatica” and “Totentanz”, my performance master’s thesis [the first ever] with an electronic score by Warner Jepson and settings by Cal Anderson.

My own interest and research in the eastern religions and metaphysics became an inspiration for ballets related to Buddhism, Vedanta, the Upanishads, the Tao, the I Ching, and the Tibetan Book of the Dead. “The Awakening” [1968], Warner Jepson; “The Way” [1969], Toru Takemitsu; and “Genesis ’70,” Terry Riley, were all created for the San Francisco Ballet and reviewed enthusiastically by the local press.

Lew Christensen (the SFB’s artistic director) and I had a diametrically different approach to working with dancers and for creating choreography. He was a very cool and aloof director, rarely socializing with his dancers. He and his colleagues made up a very conservative administration, seemingly uninterested in connecting with the community at large, rather favoring influences from the East Coast and the New York City Ballet

On the other hand I had always been a member of the SF dance and arts community since my days as a college student and continued being so even with my SF Ballet job as ballet master and associate choreographer. My relationship with the dancers was very close and personal, as it has always been, and as such, I was able to interest them in other projects outside of their SFB duties, I was also extremely interested in bringing local San Francisco talent into the artistic picture of this company.

We did not have permission to credit the SF Ballet for our group; so we became an underground company, “The Radial Theater.” We performed at several venues in the Bay Area including The Oakland Museum, the newly formed Project Artaud (later Z Space), and the newly opened “Exploratorium” [another first]. We participated in the opening of the new wing of the S.F. Art Institute with Warner Jepson’s electronic sounds and Ray Anderson’s Holy See light show company on the roof of the new structure. In another “happening” we danced around the Coit Tower while Margaret Fabrizio played the Moog Synthesizer on Twin Peaks, an event which was broadcast.

We also did a multi-media dance week end event at the “Family Dog” on the Great Highway with rock groups, and light show companies in which we used plastics, smoke, projections and even vacuum cleaners which would blow air into the smoke and plastics, creating fantastic psychedelic imagery with the music.

“Genesis ‘70”

“Genesis ’70” premiered May 25, 1970 at the San Francisco opera house was to be a meeting of several creative artists who would contribute fully to the whole production. It was the culmination of several years of producing dance works related to my esoteric studies and experiences. The Summer of Love in 1967 was one of the stimuli for subsequent ballets of mine but I did not specifically use it as a reference. I attended the Human Be In and many other such events, which were reflected in my works by feelings of joy, interconnectedness and spiritual awakening.

This work set to the serial music “In C” by Terry Riley, used the Moog Synthesizer for the first time in a symphony orchestra. The setting by Paul Crowley included rear projection screens and Robert Ellison’s “The Garden of Delights” light show company, which projected from the rear, the front and the sides onto the stage. Forty dancers dressed in white unitards appeared led by prima ballerina, Jocelyn Vollmar, took us through a progression of the five elements— earth, water, fire, air and spirit.

Each elemental section was lit accordingly with colors and textures projected upon the stage and dancers who also were able to flash color and textures out to the audience with reflective discs as well as catch the patterns on the reverse refractive sides. At one point, three men emerged from a “nest” of these discs crawling through unrolling plastic tubes to the continuously throbbing pulse of the Moog synthesizer leading the orchestral score. Since the musical themes were never repeated in a regular sequence, there was no way in which the dancers could anticipate any melodic connections. They were acutely conscious of each other and would need to watch, wait and breath together to begin a series of choreographic moves and patterns.

It created a “here and now” feeling of timelessness—of being in the absolute present moment, which was translated to the fascinated audience, some of which were ecstatic and others disturbed by the overwhelming flood of movement, color and textures and sound. We were not trying to create anything outrageous or scandalous, but the results of the performance were extremely exciting with an audience response that was unanticipated by all of us.

Russell Hartley, the Dance Magazine critic, compared the controversy to what the 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” must have been in Paris. Other local critics were also positively affected by the performance and noted that it boded well for the future of the company.

A personal involvement with Chet Helms and other cultural community members of the Haight-Ashbury caused an increased interest in attending our ballet performances, and by the time “Genesis ’70” opened, it seemed like the entire “Flower Power” community had come—-fringe, bell bottoms, paisley, long hair, patchouli and all, dressed to their very best. It was a hippie invasion to the usual ballet attendee and many were offended by this manifestation of the youth culture at their staid opera house.

This program opened with my Apollonian “Joyous Dance”, followed by Lew Christensen’s mysterious “Fantasma” and ended with the Dionysian, “Genesis ‘70”. It was a well-balanced and exciting program, but after it was all over, we had a company meeting to discuss future plans. I was informed that although the ballet guild really liked my first ballet, they just couldn’t enjoy the last and they did not want “that” audience to come to our shows.

That was a stunning reproach since every effort that I was making was to attract the youth audience to our productions, and we were succeeding. The unexpected controversial audience and critics’ reaction, both positive and negative, was responsible for the final rift in my relations with the Ballet, which rejected its new popular appeal and decided to follow a more conservative path. They even cancelled the summer season being held at the ample City College Theater in favor of retreating to the smaller confines of their studio theater, apparently because of fear that it would attract more of that hippie community at the college.

This rejection was incomprehensible to me, and several of the critics who were reviewing our shows and noticing our success in being in tune with the present social and artistic movements.

Even though I was receiving most of the press’ notice for my new works, I became the company pariah, the invisible element of the company, at times deleted as a company member. My name was omitted from a company roster in April 10, 1970, even though I was currently creating two world premieres, “Joyous Dances” and “Genesis ‘70.” Another time, when Lew was ill and I directed and re-staged his “Beauty and the Beast” for television, I received neither extra compensation nor mention in the credits.

My home, The Villa Satori, which I bought in 1967 during the “Summer of Love,” became known as an artist commune. In June of 1970, when I resigned from the San Francisco Ballet, it served as the center of operations for our new company, the San Francisco Dance Spectrum, which was born fully formed with dancers, choreographer, musicians, designers, technicians and a focus of interest by our local dance critics. With this company, I was then able to continue to follow my muse, create some of my most important ballets and to perform in most of the principal venues in the Bay Area.

That’s another chapter!

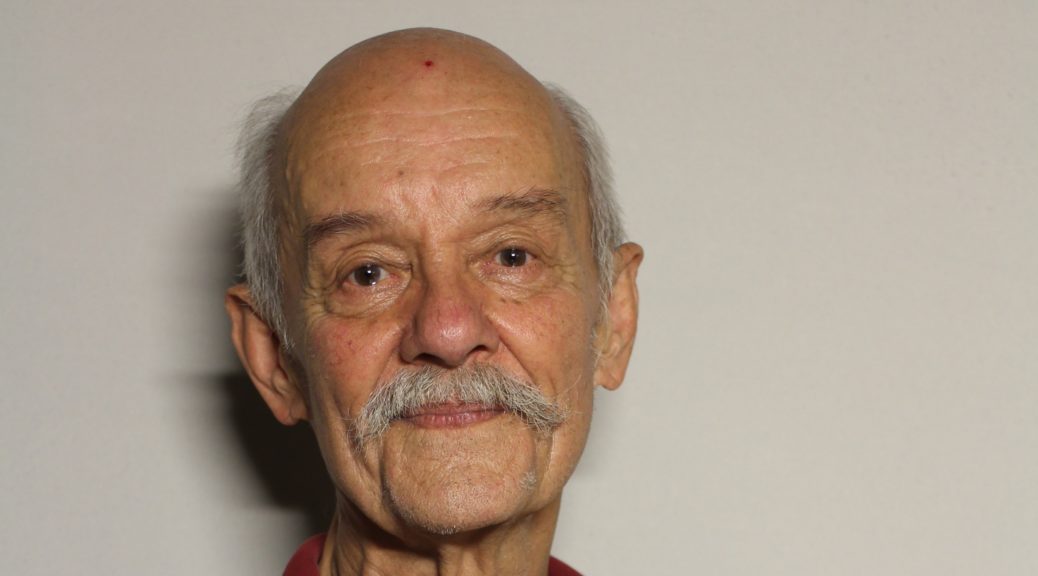

A native San Franciscan, Carvajal is of Philippine-Swedish extraction, having earned a master’s degree in creative arts at San Francisco State Univ. He had danced with European companies for a decade before coming home in 1964 to the SF Ballet.