MAHLER’S PASTORAL METROPOLIS

Writing a symphony, composers are like architects designing a new city.

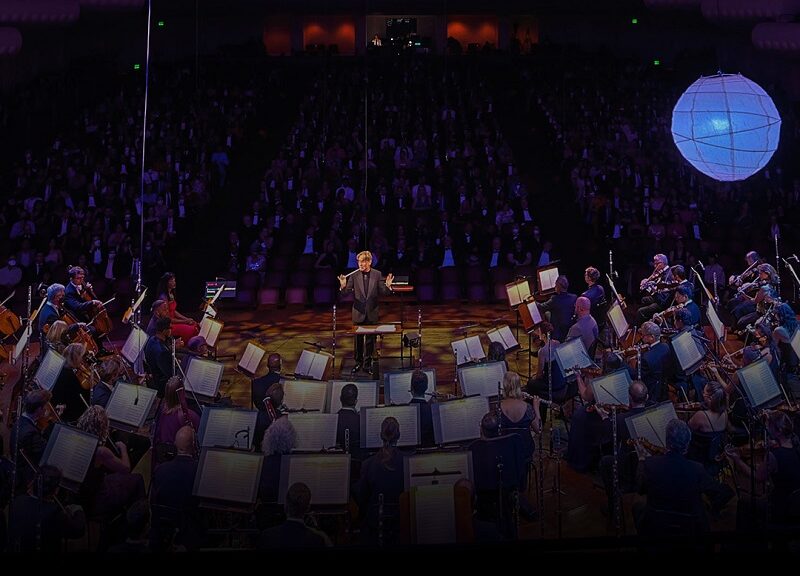

But not Gustav Mahler. In his Symphony No. 3, he created a musical metropolis, @ 100 minutes running the length of two or three normal symphonies. The oversize 111-member orchestra, with doubled winds and harps, a paired set of timpani within a seven-member augmented percussion group, plus singers, add up to a bulging score more like four symphonies in one. The extravagance was unprecedented, with no regard for production costs. At the end, like the cherry on the sundae, three percussionists haul out oversize cymbals two feet in diameter for a single, colossal crash.

Created mostly in summer “holidays” of 1895-96, the work had Mahler in an unparalleled burst of inspiration, wherein parts of the resultant score actually had to be siphoned off to enter his next (fourth) symphony. Holed up in a small summer cabin by the Salzburg-region’s lakes, Mahler required absolute silence, with helpers chasing away birds and noisy children.

Mahler’s musical metropolis was above all pastoral, with subtitles alluding to summer, flowers, animals, love, even angels. And yet the five-movement opus is bursting with passion and drama, even providing funeral marches. The emotional extremes of late romanticism were never more expansively spelled out.

I’d propose that Mahler was, perhaps unconsciously, also plumbing human emotions in their many extremes, so artfully alluded to in his orchestra and singers. Why else, in Part I alone, the sequence of assertive horns, funeral march, sunny trombone solo, dissonance, upbeat march (a la “Star Wars”), total exuberance, tempo shifts, and a murky, pensive transition toward marches both depressing and upbeat?

For this grandest of season finales however, it finished with sheer bliss June 28, Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen dashing upstage and hugging his soloists on trumpet (Aaron Schuman) and trombone (Timothy Higgins), who both came through splendidly. The trumpeter had a dual role, also playing a cornet offstage to simulate the post horn.

Part Two is a four-movement smorgasbord. It ranged from the mezzo Kelley O’Connor’s interpretation of an ultra-soft Nietzsche midnight poem to an exuberant combined 50-member womens’ and youth chorus for the crowning Angels’ Song. By then, if the Gates of Heaven don’t actually open up, at the very least Mahler had completed his biggest composition ever, presumably heralding enough income to pay for those bucolic and inspiring lakeside summers near Salzburg, Austria in one fell swoop.

MUSIC NOTES—The financial plight of the debt-ravaged SF Symphony, had the musicians once again leafleting arriving patrons. While voicing their strong support of Salonen, hoping that he will delay his 2025 departure, they also deplore the program cutbacks at SFS, done to reduce the growing deficits. The SFS debts, prompting Salonen’s 2025 departure, has gotten media attention as far away as New York City….The oddity of conductor Salonen’s sitting down for a five-minute break between parts one and two were not due to fatigue, but rather a specification in the score—-perhaps more motivated for the perspiring musicians than the conductor.

S.F. SYMPHONY and choruses under Salonen in Symphony No. 3 of Mahler June 28-30, Davies Hall, San Francisco. SFS season finale. For SFS info: (415) 864-6000, or go online, www.sfsymphony.org.