GOING TO BAT FOR BARTOK

What were the outstanding orchestral works reacting with eloquence to tragedy or major losses of life in the 20thcentury?

Berkeley composer John Adams cited several of them in writing for New Yorker magazine (dated Dec. 11), pieces written by Shostakovich, Schoenberg, Britten and Richard Strauss, in reaction to massive losses of life in world wars. He also emphasized his own turning down a commission to write a 9/11 piece, saying it was too immediate for New York City itself, with many relatives of victims in attendance, still in shock.

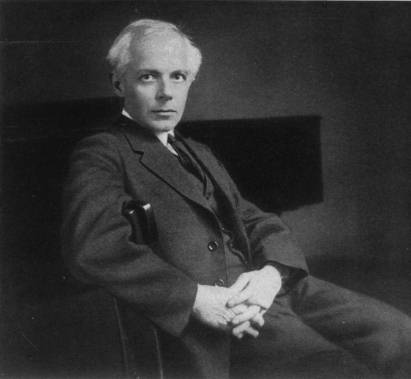

Adams created a formidable list—yet one with a notable omission from that same period. Béla Bartók’s five-movement “Concerto for Orchestra” (1943) was eloquent, arguably his great masterpiece, written at the dark time of, barely, the first Allied troop landings in continental Europe leading to eventual liberation and peace. Given Bartók’s poverty, his forced emigration and his homesickness for Hungary, a nation then caught between Nazi persecutions, the subsequent Soviet invasion and decades of Communist suppression, the 40-minute work is uniquely timely and imposing.

Clearly he reacted strongly against the carnage of wartime and, as a nationalistic composer and ethnomusicologist, he greatly missed his homeland. Two short musical quotations from Hungarian sources in the concerto are telling among his shattered memories, most notably the sentimental song “You’ll Find Me at Maxim’s” (yielding to a bitter Bartok musical after-statement), from the operetta “The Merry Widow” by Léhar. Farther along, he quoted a similar musical segment from the “Gypsy Princess” operetta by Kálmán, “Szép és gyönyörΰ Magyarország” (Hungary Beautiful).

The war weighed heavily on Bartók, as it did on other composers cited by Adams, each with a distinct approach to a commemoration. For Richard Strauss, his “Metamorphosen” (Metamorphoses) alluded in a delicate, heavy-hearted way to the destruction by bombers of the wondrous arts city of Dresden. For Shostakovich, his “Babi Yar” Symphony No. 13 with vocals expressed the horror over the massacre of some 33,000 Jews by Nazis at the killing-fields site near Kyiv, Ukraine. And Arnold Schoenberg in his brief outcry “Survivor from Warsaw” had a narrator expressing his similar revulsion of high intensity over attacks in wartime Poland. Finally in his eloquent, poetic “War Requiem,” Benjamin Britten commemorated the immense loss of life among the trench-warfare soldiers of World War One.

Adams lamented the absence of similar American works of protest or horror reacting to tragedies. Maybe that too will come, reluctantly, as a consolation after some future misfortune of great magnitude.

UNSCRAMBLED COMPOSERS—There are two similarly named but unrelated American composers on the scene these days: The one here, John (Coolidge) Adams, was born in Massachusetts in 1947. The Alaskan Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams was born in 1953.