ECSTASY AND DESPAIR, SYMPHONICALLY

How can so much exuberance emanate from one of the most depressing large-scale symphonies ever written?

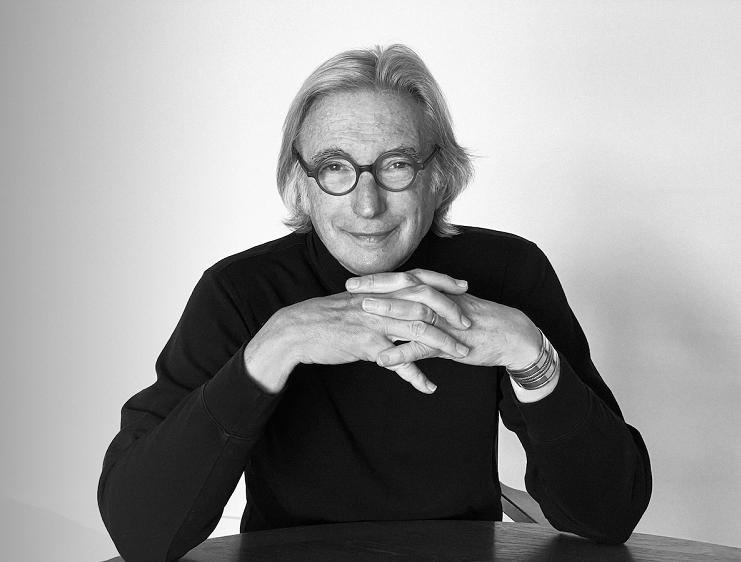

Easy. You put a beloved ex-maestro like Michael Tilson Thomas back on the podium. Upon entry, the revered 78-year-old conductor got a standing ovation from the near-sell-out crowd. And at the end, the fired-up patrons accorded the S.F. Symphony and him an inordinately rare six-minute ovation.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) himself would never have believed it for the deeply aggrieved Sixth Symphony of 1904, which had left the ultra-emotional composer sobbing uncontrollably on first hearing. Here was the ultimate late romantic, carried away by his own music—so searing in its impact, he could not contain his emotions.

Analysis from this (distant) vantage-point seat suggests it all dealt with premonitions of death. His heart was failing, presaging his demise at age 50. The finale’s sledge-hammer blows on a resonant wood box, executed by percussionist Jacob Nissly with a Donner-sized sledge from the balcony a full floor higher than the stage, are unique in music as such premonitions, even more so than the death-rattle bass trill interrupting the melody of the Schubert Piano Sonata in B Flat Major’s opening (that being the speculation by pianist Andras Schiff).

We have to thank Mahler’s unquenchable work ethic, and presumably the Almighty, that he was around to write three-plus additional symphonies, along with vocal works. But none of the later ones resonated with such tragedy as the music of the Sixth.

Still, it’s a thoroughly engrossing, mammoth-scale opus whose complexity and giant-sized orchestra draws you along with it—- passionate despair be damned. The Sixth is a multi-dimensional wonderworld full of trapdoors, all 90 minutes of it. The long opening movement is a dour military march toward some lemming-like goal. The Scherzo has another funeral march in minor with big brass gestures and snare drums. Only the appearance of the sweet-tender Ländler (Austrian waltz-predecessor) mitigates among the abrupt gearshifts, some of them on tiptoe.

Finally the slow movement arrives with its eight (!) French horns and a woodwind chorale, all a genteel, spacey escape in the midst of this voyage of heavenly length. The multitude of emotions is like itself—only that Mahler suffered the extremes more than perhaps any one.

The boisterous finale offers tumult via the ominous box-smasher, plus horns playing bells-up in a raw sound mode. The frenzy subsides now and then, enabling cowbells to sound out offstage. Currents and crosscurrents endure until a brassy ending, still with strings bowing away tirelessly, comes as you had never dared possible, with fulfillment and a measure of relief.

The performance was inspiring. Most notable is that all the augmented sections, like four clarinets, two harps, six trumpets, etc.—coalesced into a coherent whole without loose ends. This was an achievement of which MTT could be proud into his retirement days, if they ever come.

MUSIC NOTES—MTT’s return to action has come this season with much cheering, as only optimists could have predicted given his precarious brain-cancer operation (glioblastoma) of a year ago….MTT programmed more Mahler than any of his predecessors as SFS music director….Three cheers for the unsung tuba: At the end of the March 30, MTT accorded the first of the orchestral bows to Jeffrey Anderson, the principal whose tuba too often is taken for granted.

`San Francisco Symphony with M.D. Laureate MTT in Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, March 30-April 1. Davies Hall. S.F. For info: (415) 864-6000 or go online, www.sfsymphony.org.