MELDING BALLET WITH JAZZ

Gregory Dawson, the leader and choreographer for the dawsondancesf ensemble, nurtures the belief that jazz and ballet can create a happy, conflict-free partnership. Dawson wants his ballets to emulate the improvisational aesthetics of jazz, in which musicians in turn riff off of a basic theme or motif, first the sax, then the trombone, then the piano, before putting all of them together again. Something similar with the choreography: take a movement trope, riff on it, then move on to the next trope, the next solo, the next duet, the next ensemble. The musicians play brilliantly and the dancers perform excellently.

His ballet/jazz result struck me as less “cutting edge” than mainstream.

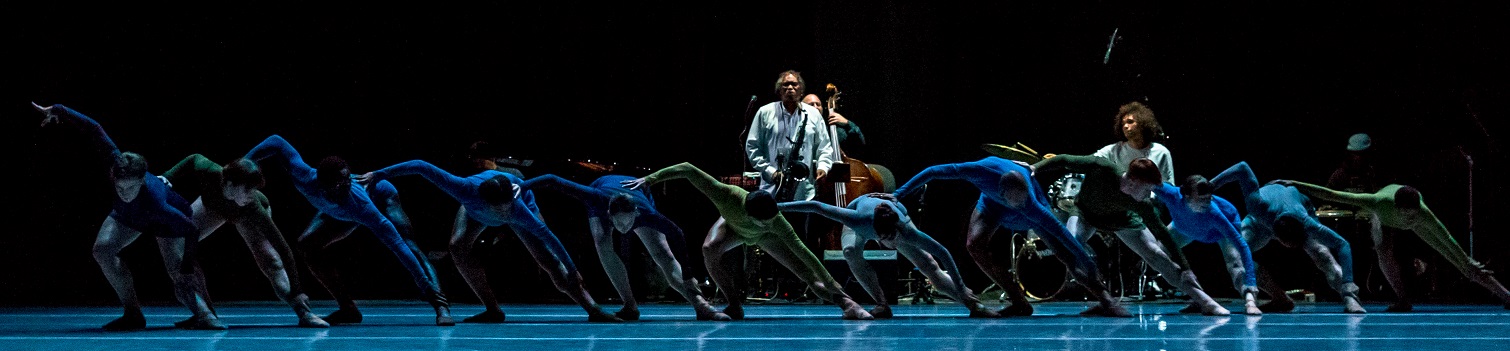

On August 24 and 25, dawsondancesf, whose home is only a few blocks away on Seventh Street, appeared at Yerba Buena Center with a program of two pieces, each about forty-five and fifty-five minutes long respectively. The ensemble consists of twelve dancers. The production is a collaboration of Dawson with the saxophonist and vocalist Richard Howell and his sextet, Sudden Changes, on stage with the dancers throughout the production, even playing during the intermission. Indeed, the sextet provides the only real scenic environment for the show. The visual aesthetic here is strictly minimalist, reinforced by David Schimmelman’s utterly quiet, non-dramatic lighting.

The first piece, Floating in Mid-Air, consists of nine dances, preceded by a raucous overture. The dances have titles, such as “Jube,” “Funny Daze,” and “Charlie Mac,” but the titles seem arbitrary and do nothing to clarify how the spectator should “read” the dances. But the dances do not relate to each other in any conventional narrative sense. The first dance is a solo, performed with snakelike pliancy by Isaiah Bindel, accompanied by Howell’s solo saxophone. Bindel is an astonishingly lithe, sleek, and athletic dancer, and he zoomed around the stage performing exuberant acrobatic contortions of his torso while his arms swirled and sometimes his legs slashed the air like large blades. The music was loud and explosive, and largely so throughout the concert, with plenty of driving percussion by the amazingly talent drummer, Ele Howell, Richard’s son. The music is not “cool” jazz; it seems more inspired by the protesting shrieks and cries of 1960s jazz revolutionaries like Archie Shepp. I can’t say I gained from the piece any insight into the theme of “floating.” Following Bindel’s solo, the entire ensemble gathered on the floor and performed various languid movements before rising up and forming a frenetic, swooping, jolting, though almost entirely unison tribe. Subsequent dances in this suite provided opportunities for members of the ensemble to display their kinetic skills. Lauren Worley performed a solo, Bindel and Madison Otto performed a duet, Worley and David Calhoun performed a duet, Bindel and Erik Debona performed a male duet, and the piece ended with another frenetic ensemble piece. At moments, dancers (Calhoun, Elizabeth Pinschel, Bindel) performed solos while the ensemble moved in unison behind them or to the side. Evidently, the idea was to show how members of the group could step outside of it, do their own thing, and return to the group without suffering any discord. Drama is absent.

Dance presents here an image of community without any internal tension: dancers do not perform solos because the group has expelled, alienated, or ostracized them but because they must show that they can move outside of the group without repercussion. Re-entry into the group changes neither the group nor the soloist, for the group easily provides space for members to be apart, and members always rejoin the group without altering it. The duets also reject drama. In all of them, the dancers enact a condition of equilibrium. They complement each other, they echo each other, they help each other, they support each other, and they equal each other. As with the ensemble numbers, there is no sense of any power struggle, no suggestion of one partner trying to dominate or submit to the other, no reversal of power, no intimation of one dancer trying to escape the other, no idea of one abandoning the other, no implication of how hard or amusing or frightening or ecstatic or even dangerous it is for two people to form a pair. The choreography thus has a sameness to it, like the costumes: the dancers all wear dark, nondescript gym-type clothes, designed by Joan Raymond, although for a couple of dances the men wear only skimpy black briefs to show off their muscular physiques.

The second piece, Mangaku, was a premiere and consists of thirteen dances, again with cryptic titles, such as “Mother Earth,” “Dance on the Mountain,” “Mix Olyo,” and “Dude in Black,” and again involving alternation between duets, ensembles, solos, and (very briefly) a trio. As in the first piece, the music changes tempo, but the intensity remains constant, so that all the pieces seem like exuberant wails, gonzo cheers, celebratory cries, and pulsating raptures. In one piece, Howell sang over and over again the phrase “All I have to give is my love,” reinforcing the perception that repetition is fundamental to the “giving” that forms collaborations and communities. For Mangaku, the dancers wear mostly body-contoured, bright blue tunics to achieve a somewhat more cheerful athletic look than in Floating. Yet Mangaku feels like an extension or even recycling of Floating. The qualities I have ascribed to Floating are the same for Mangaku. The solos, duets, and ensemble numbers apply the same movement tropes and abstract bodily configurations as in Floating.

Yet the hostility to drama and theater in these works makes them seem as if they were entirely conceived within a hermetic studio insulated from anything outside of it. The dances and dancers make no reference to anything outside of themselves. It is like building a concert out of studio exercises; the choreographer extracts “interesting” movements from studio exercises and combines them with other tropes into “riffs” and variations that demonstrate the pliancy of the dancer. This is dance “about” dancing and dancers, an aesthetic repetitively asserting that dance is a condition of freedom, of exultant liberation, achieved through the sequestered, egalitarian community of the dance studio. But in the studio-enclosed, postmodern dance culture, dance is a sign of freedom only when it excludes all conflict within itself, all power dynamics within and between bodies, and any idea of dance as a threat, danger, or emblem of dismay. While many in the contemporary dance world idealize this studio-enclosed creativity as the foundation for a utopian society, the dances that emerge from the studio do seem to focus on a very narrow range of emotions: exultation, energetic enthusiasm, pride, celebratory unity. This makes dance seem a little too harmless and perhaps too “friendly” for its own good.

Jazz and ballet have not enjoyed a consistent, vigorous relationship, and one might even say that ballet has achieved a more comfortable relationship with pop music than with jazz. Jazz thrives on improvisation, while ballet celebrates the deterministic scoring of music and movement. Perhaps some sort of powerful drama might arise from exploiting this conflict between the improvisation and inscription of performance.

dawsondancesf: http://www.dawsondancesf.org/performances/