CELEBRATING LOU AT 101

The happiest composer I ever met was the prolific Lou Harrison, whose centennial celebrations, like his large output of music, couldn’t all be squeezed into 2017. The Harrison joy persisted up to Jan. 24 with a small-ensemble concert of amazing variety at the inviting and sold-out Strand Theatre.

In the end, doing even an intimate all-Harrison concert comes down to finding exotica like “junk-yard” instruments, gamelans and even genuine Studebaker brake drums to provide the ever broader sonic array needed for Harrison, the inventive Bay Area product who passed away in 2003.

How many Harrison musical styles were there? First the rambunctious all-percussion pieces he turned out with John Cage; then ultra-serious serial tone-row music; four symphonies; instrumentals retuned from equal temperament to the earlier just intonation that his ears dearly loved; and Far Eastern influences, ranging from India’s rice-bowl percussion to gamelans from Indonesia. Most of these were dominated by his pacifism (political and otherwise) and gentle don’t-ruffle-me personality—a Northern California phenomenon contrasting sharply with the highly energetic and even frenetic East Coast or New York style.

Fortunately, Harrison never had to tussle with today’s electronic technology, which had several of this night’s musicians wrestling with their scores on balky electronic screens. “I just charged this iPad, and now it’s gone dead!” was the exclamation of frustrated pianist and concert co-organizer Sarah Cahill. One of the musicians handed her what may now be an endangered species: a score printed on paper, which was the only form that composer Harrison had used.

The clash of the future with the past. So far, the score stands Past 1, Future 0.

The Winant Percussion Group dominated the night with myriad instruments producing an amiable clickety-clack, notable for the rare jalatarangam from India—-a set of untuned bowl struck with slender sticks, alluring in their fast-paced but delicate flight. There was an African thumb piano and, in the touching “Threnody for Carlos Chavez,” a large gamelan ensemble backing the retuned viola of Paul Yarborough.

The Studebaker brake drums? Years ago Harrison had told me that the 1936 Studebaker auto had the most resonant brake drums of any auto for percussion; later brake drums used an energy-absorbing alloy that ruined the musical potential.

Most of the music fit Lou’s persona: stately, unwavering, meditative/hypnotic, consonant and at times patterned after a slow procession. The jalatarangam was one of many accompaniments to a violin-piano pairing of “Varied Trio” of 1986. At the other extreme, the “Song of Quetzalcoatl” of 1941 had an imagined ancient Aztec music for percussion using those brake drums.

On the less-than-cheery side came the “String Quartet Set” based on music of the 12th century German minnesinger Walther von der Vogelweide in a minor mode.

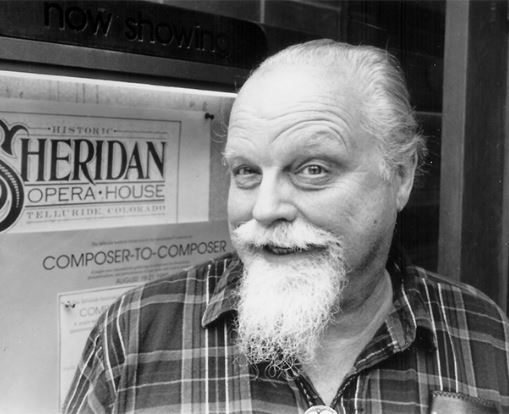

In the end, the great Harrison contribution to music was a massive expansion of the composer’s instrumental palette, rediscovery of both renaissance tunings and Far Eastern musics, and, simply, having a jolly good time in the process. His legacy remains alive in one East Bay college where the piano retuned for his works adamantly refused ever to go back to conventional tuning. Harrison loved keyboard, and clearly this keyboard loved Harrison forever. And somewhere up there, with that Santa-Claus laugh and beard, Harrison is having a ball.

Lou Harrison Centennial Concert (a year late), Strand Theatre, S.F., Jan. 24, presented by San Francisco Performances as part of the innovative PIVOT series. For SFP info: (415) 392-2545 or go online.